-

-

1. Friendships and Family

WENG-CHOY: Friendship has been a major theme in my work for a long time. Years ago, in an essay on art criticism and biennales, I addressed the accusation that I only wrote about my friends. While not entirely true, over the years I have regularly returned to discuss a few artist-friends, and less often have I written about artists new to me. Unlike some others, who can almost promiscuously move from one artist to the next, my kind of critic is like a polygamist, “wedded” to each subject they write about. There’s something about the intimacy of writing about someone you’ve been speaking with and listening to for many years.

Indeed, we are having this conversation less because we may share artistic or intellectual interests than because we have a very good friend in common, and I’ve known your sister for a long time.

I remember once when a friend set up a meeting between me and a young artist. Afterwards, I felt it was like a waste of an introduction. It was just a professional courtesy; it didn’t offer the prospect of new friendship. You don’t have to already be my friend to interest me in writing about your work; rather, for me, wanting to write about your work and wanting to become your friend are very often the same thing. I am motivated less in finding something “interesting”, professionally and intellectually, than in wanting to care about you and your work intimately.

WEI LENG: Many of my projects and work have been of relationships, and build because of relationships—my own and those of the people around me. Like what you have said about not necessarily being moved by an intellectual point alone, I have often functioned thinking about the community and people around me—how their relationships affected the choices they made, the places they moved to, how they lived their lives. Many of my projects have also begun with my family because I have, for most of my adult life, lived away from my family, in different places. This has over the years also made me ask myself how a familial relationship is different from one with a friend, and the intimacy that can happen between family, friends, and also with people one meets in passing. In this way, I have been driven over the years to think very deeply about how one can understand the person one is next to, and the person one is related to. How can one understand one’s family member, one’s friend? How does being related even influence how one can think about a place, what one can value? This has made me very aware of, and I’ve worked a long time through, identity politics, and I’ve questioned the value of group identity politics, especially in relation to the politics of an individual.

I have not had much interest in taking abstract, large topics, and creating an “art project” based on those topics. I have instead been interested in how some of these issues could be considered through one’s everyday, how they manifest and affect one’s family, or friends, or livelihood. In this way, I skirt the grandiose tropes, and perhaps seek to articulate life through its closeness, which, admittedly, is sometimes harder for me to approach.

-

-

-

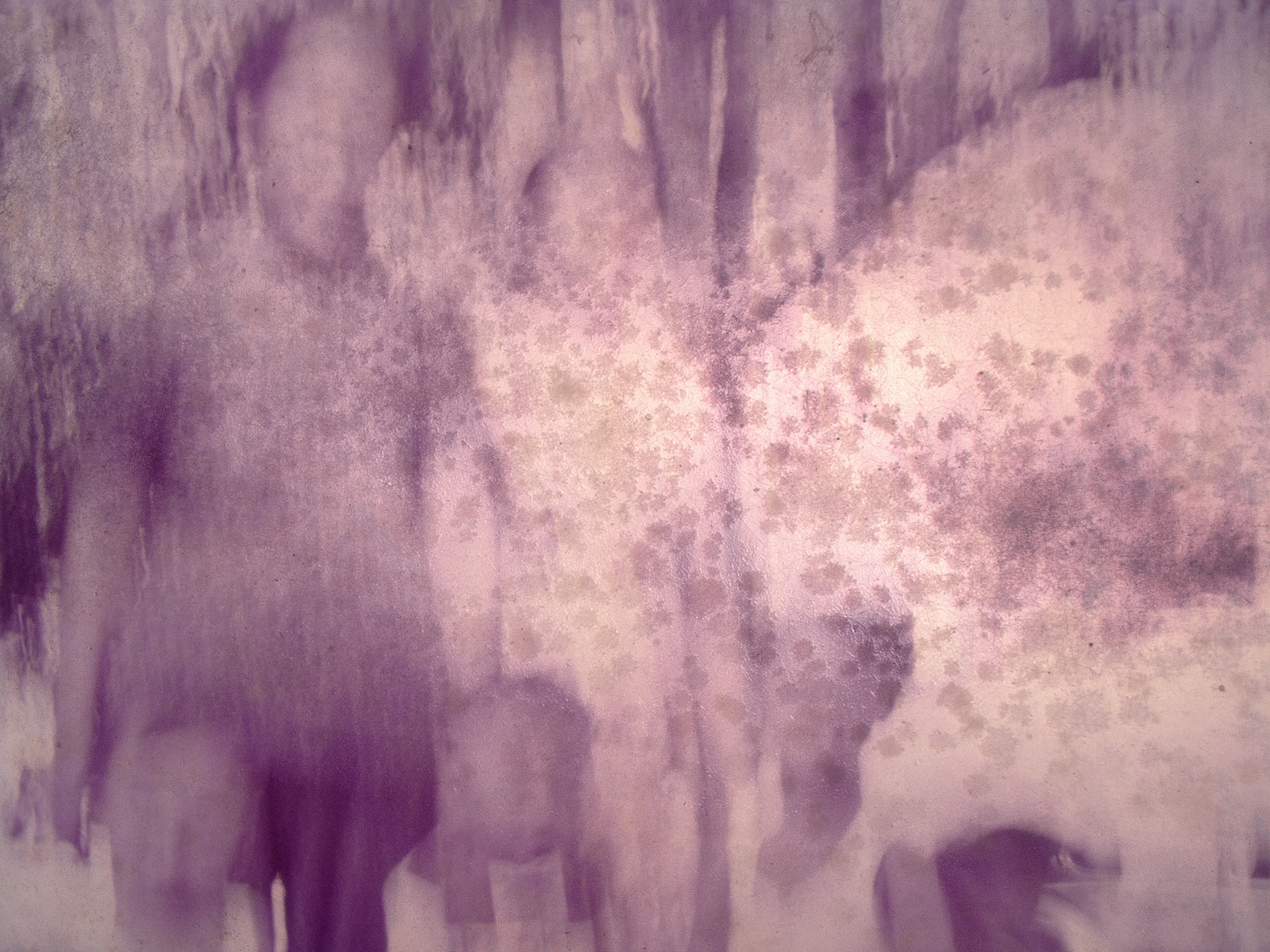

WENG-CHOY: This is the beauty of analogue photography, in contrast to the digital: the indexical relationship of film to light, and how film is subject to chemistry over time.

WEI LENG: Yes it is. And in this current iteration of working with the material, I step away from the sedimentation and compression of history—an environmental history, a migratory history, and a familial history. Instead, I move towards how technology influences the outcome. The technology of recording, in terms of the capture, rendering, and also the chemical technology of the analogue transparency process. These traces become analogous to keys to the systems that shape us, hold us, and bind us. They create means of looking that remind one that images, and documents, are subject to modes through which they are made.

How do the transformations here then speak back to that micro-history? In many of the works, the original image in the photograph is sometimes obscured. The image surface is smooth. The colour shift induced by time and climate also creates a surface opacity that one can glide across effortlessly. The people and places depicted are trapped in a time and place long past and unrecoverable. What then are these photo-objects? A white cardboard slide mount starts to appear like a chalkboard. An idyllic horizon burns like it is lit by fire behind a grid. My mother’s handwriting is magnified until all one sees is what it is constituted of. A seaside bench rests in a pockmarked reality.

-

-

-

WENG-CHOY: I suppose one way of framing my last question is that it’s about the distance between the artist’s feeling and the audience’s experience. This distance is important in art, because it’s often the space that allows art to do what it does. Making and displaying art is not like making an argument. In contrast to political persuasion, where you want to close the distances and come to an agreement or alignment. For example, in US politics today, in the fight to protect a woman’s right to choose an abortion, there may be a range of different perspectives and opinions on the complex issue, but after all the discussion and argument, action requires a decisiveness, and not ambiguity.

Another way to put it is that I don’t think the point of showing your work is for audiences to somehow get all the personal history references. And yet, somehow, still, the point is that the audience will experience these photo-objects as intimate things with their own rich micro-histories. It’s as if your aim is not to tell a specific story of your parents’ lives—a story that does not quite include you—but to convey that feeling of something that is intimate to you, and also distant from you. And to convey the tensions between intimacy and distance. And that somehow when the audience experiences the work, this feeling gets reproduced in them too.

WEI LENG: Yes, Weng. I would say that the personal historical information and its representation are not the main point. The narrative I consider here is not a storied one. Instead, it is one that wonders about the idea of that intimacy, or that tension between intimacy and distance, as you put it. When what we can hold on to are these split-second moments, when these fragments can show us these lives lived, and simultaneously remind us of everything that we cannot know, how can they then be pieced together? Can colour, abstraction, and technological artefacts open up what they can mean? For example, the abstraction in the works create a space for remembering a past—flickers of a past that pulls at nostalgia, indicative not of particular events, but instead moments that build toward the present. Similarly, the colours, like the technological artefacts, speak to particular systems of creation and their inhabiting particular geographies and climates over the years. These combine to bring us into a present that is heavily laden with that history and life, and yet subject to its rearticulation, and transformation.

As I write here, it feels as though we have gone full circle. And we have, in a way, come back to your thoughts at the start of this conversation on artists and their work and what is important to you. How does one not make work that an audience just looks at and is interested in only intellectually or topically? How does one make work that speaks to so much more, that one hopes the audience can care for intimately?

-

LEE WENG-CHOY is an art critic now based in Kuala Lumpur. For over twenty years, he worked and lived in Singapore. He is working on a series of conversations called Friends with Disagreements—forthcoming with Stolon Press—and very slowly working on a collection of his essays on artists, The Address of Art and the Scale of Other Places.

-

The micro-history and the photograph: Lee Weng-Choy in conversation with Wei Leng Tay

Past viewing_room