The Balinese artist’s paintings subvert old sources to tell new tales.

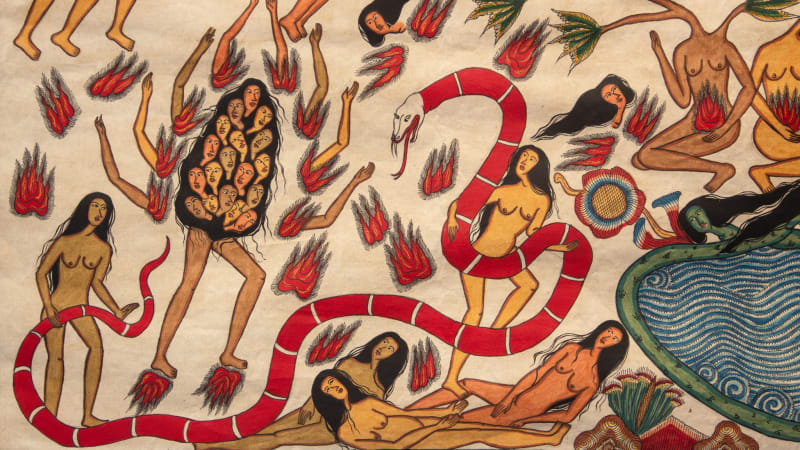

Allegory of Archipelago (2023), currently showing at the Bienal de São Paulo, is a teeming, churning phantasmagoria of heaven and hell and everything in between. Created by Balinese artist Citra Sasmita, the work takes the form of a largescale installation comprising several suspended painted scrolls. Central among these is a nine-metre-long canvas floating horizontally, depicting a tripartite cosmology starting with a harmonious Edenic realm of supersize tree- and snake-women, then descending to an earthly zone of war, before ending in a fiery underworld of heads on stakes and figures in boiling cauldrons.

This mythological view of the Indonesian archipelago is combined with a pointed critique of the country’s violent colonial legacy. In front of the scroll, on the ground, is a golden figure of a kneeling Caucasian man holding a money bag. The statue is a replica of an actual figure that was placed in front of the gate at the royal palace in Klungkung, the last Balinese-kingdom holdout against Dutch invaders during the early twentieth century. After razing the palace and destroying its original Hindu statues at the gate in 1908, the Dutch replaced the them with figures of white men to be worshipped by the local population. In the artwork, a rope runs from the bottom of the painted scroll and winds around the figure’s neck in a noose. The gold-plated squatting idol – symbolic not just of colonial greed and conquest, but of cultural brainwashing and perhaps, as recent history has demonstrated, even the overarching power of Western neoliberalism – is gnomish, vulgar, powerful.

Sasmita’s work is contemporary in that it takes a posthuman feminist stance; besides fighting for gender equality, she goes deeper to destabilise the assumptions underlying other binary structures, such as anthropocentric biases, and hierarchical categories of nature and culture, the human and the nonhuman. One nonhuman archetype that Sasmita often taps is that of the snake, which holds great symbolic meaning in Balinese lore and Indonesian culture. Her protagonists are often depicted with snakes encircling them or hybridised into half snake, half-women. In Hinduism and Buddhism, nagas are a powerful semidivine race that can appear as human, a partial human-serpent or a whole serpent. In kundalini yoga practice, the snake is the image of vital energy in the cosmos, and is coiled up at the base of the spine.

Snakes will play a huge part in her upcoming work in the Thailand Biennale in Chiang Rai. It will be a quasi- shrine to feminine energies – a circular structure with 900 braids of red ‘hair’ (made from rope) hanging from the ceiling. The red hair is inspired by the story of Draupadi, the main female protagonist in the Mahabharata. In certain adaptations of the story, she washes her hair with her brother-in-law Dushasana’s blood in revenge, after he had molested and tried to disrobe her in public. Referring to the purifying nature of righteous anger, the end of every sinuous blood-red braid in Sasmita’s work culminates in a snake head made of brass, connecting justice-seeking vengeance with a symbol of divine energy.

Citra Sasmita’s work can be seen in the Bienal de São Paulo through 10 December, the Thailand Biennale from 9 December to 30 April, and the Biennale of Sydney starting 9 March through 10 June