-

A painting’s survival, the painter Jonathan Nichols told me recently, depends on its capacity to connect.What does he mean?

-

At first, as I stood in the small, carpeted room that currently serves as his studio, at the back of his paved garden in the regional Victorian town of Bendigo, I took it to mean that a painting must take hold of its viewer if it is to live. It must act on them, lodge itself in his or her mind. From this perspective, a painting is a part of a circuit, or a node in a network. We – that is, the viewer – complete the circuit, we close the network. The act of looking imbues the object with life; it gives it what I have recently come to describe as oxygen: that which sustains.

If this initially sounds as obscure as Nichols’s idea about connection, bear with me. Nichols speaks like this a great deal when it comes to painting, but he’s far from alone. All good painters – in fact, likely all good artists, no matter their medium – know the creeping feeling that can come from spending hours alone in the studio coaxing a work into being bit by bit. The feeling is this: that the thing before them, the thing which they have spent so long focusing their attention upon, might be somehow looking back at them, might in some sense be coaxing forth its own becoming.

-

-

-

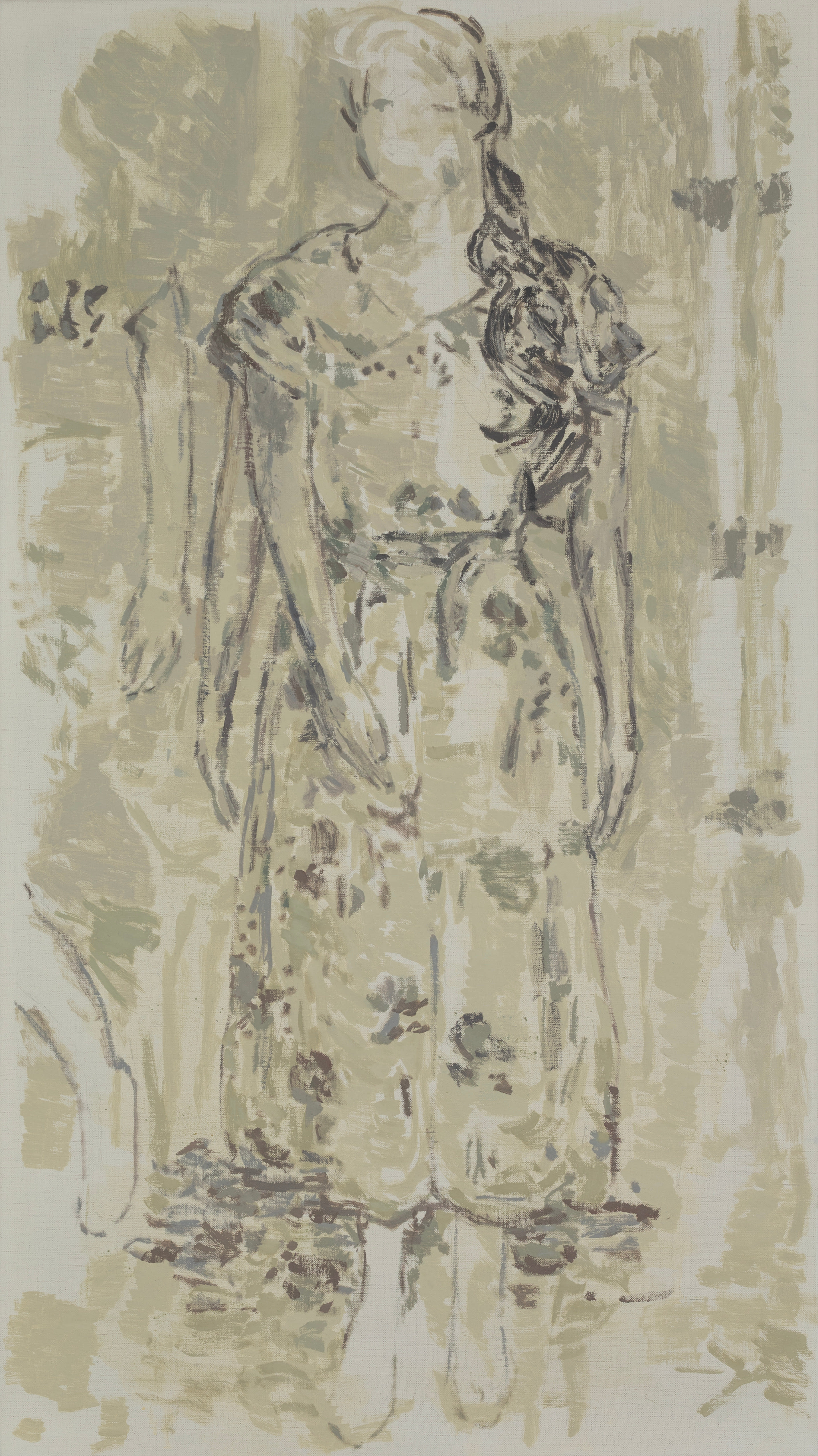

Painting in half-light, Jonathan Nichols in his studio, 2023

Painting in half-light, Jonathan Nichols in his studio, 2023 -

But look closer, let your eyes adjust. There’s colour in everything – this too is something most good painters know. Regardless of the objective colour of skin, a face can be grey or green or blue or purple. White is shadowed with a full spectrum of colour. All it takes is careful looking. Nichols’s paintings are evidence of exactly this. It’s clear they begin with source images – a picture of a stone statue, for instance, or, in the case of a number of recent works, a photograph of shop mannequins – but after that it’s all about how one thing becomes another when an image becomes a painting; how an image disassembles into its constituent parts, into colours and forms and marks that then re-group on a flat surface.

-

The idea of transmission could thus be presented as one key – perhaps the key – to these images. It’s tempting to follow this idea. One could argue that Nichols’s images are degraded by their transmission, and that this degradation says something about how images now circulate in our heavily mediated world. Download a picture of something from the internet, enlarge it, print it, photograph it: the original becomes the copy, which is in turn copied again and again. There are plenty of compelling painters who mine this kind of process, among them the American Wade Guyton, who makes abstract paintings with ink-jet printers, and thus elevates the act of transmission to a painterly subject unto itself, or the Belgian Luc Tuymans, for whom painting is a tool to reinvest photographic source images with resonant mystery. But Nichols’s work points somewhere else entirely.

-

Jonathan Nichols, Adidas (No.2), 2002

-

Nichols has a very particular painterly mark. He tells me that someone recently described it as hesitant, but as he says this he bristles at the idea. It’s not hesitant, but slow: these are different things. In fact, to look at one of his recent pictures is to wonder how long they took to paint. Often paintings can be read relatively easily in these terms: you can see the time it took the artist to produce it in the very surface of the picture. Fast or slow, decisive or hesitant: it’s all there in the touch. But Nichols’s recent paintings seem both fast and slow. At an objective level, there seems to be very little to them: a series of blunt-feeling marks in thinned oil paint that eventually gather – sometimes barely – into identifiable versions of the things they describe.

But how long do they take, really? Look closer and the information the painting offers complicates any definitive reading. I can imagine Nichols living with at least some of these paintings in his studio for years at a time. I can imagine him making one slow mark a day, and setting it aside, but I can also imagine the whole thing coming at once, and then being set aside to soak up the atmosphere (or oxygen) of the studio.

-

The Chinese artist Wu Guangzhong, who worked in both ink on paper and oil on canvas, provides one means to understand the relationship Nichols’s new work has to time. Nichols has been looking at Guangzhong’s work since living in Singapore between 2013 and 2019, and revels in the painter’s ability to feed western technique through the lens of traditional Chinese ink and brush painting. Guangzhong’s ink works, Nichols realised, consisted of concentrated sequences of virtuosic gestures. They were modulated, fast and slow.One mark might fall across another, but it didn’t cover it in the way of an oil painting. They would bleed together, with each mark laid dictating the form and painterly structure of the next. Nichols’s new paintings sublimate this lesson. Many are painted with oils on paper – the same slow marks that Nichols has long used, but now delivered in oil paint thinned to an ink-like consistency. Nichols has then bonded his paper to stretched linen, allowing the work to once more fold into another history: that of western painting.

-

-

The resulting paintings are of confounding character.They are hard and soft, fast and slow, heavy and light. In one moment, they appear leached of all but one or two subdued colours, and in the next glow with subtle shades of many. They seem both emotionally distant and vulnerable. The statues and mannequins are dead things, Nichols tells me. He says that by painting them he is making them live. He wants something to come forward in the process, he wants the images to speak.A painting’s survival, he tells me, depends on its capacity to connect.

-

Quentin Sprague is a Geelong-based writer who has worked variously as a curator, academic, art coordinator and artist. His essays and criticism have regularly appeared in publications including The Monthly, The Australian, Art & Australia and Discipline, as well as artist monographs and exhibition catalogues. Between 2007 and 2009 he lived on the Tiwi Islands and in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, where he worked for Aboriginal arts organisations.Find out more about the exhibition here.

Careful Looking: By Quentin Sprague

Past viewing_room